Q&A: Dina Esposito, Mercy Corps' vice president of technical leadership, on food and fragile states

What's the link between conflict and hunger? And why should our response focus on the long-term, even in an emergency?

Read on to learn more in this Q&A with Dina Esposito, Mercy Corps' vice president of Technical Leadership. Esposito joined Mercy Corps in 2017 to lead the Technical Support Unit and New Initiatives team, part of Mercy Corps' Program Department that is responsible for program development, program quality and thought leadership.

You can continue the conversation by following her on Twitter.

Tell us a little about your background and how you came to know about Mercy Corps.

I started my career in the U.S. government and have many years of government service including in the refugee bureau of the State Department and the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. My last job was in USAID’s office of Food for Peace, the only office in USAID that works simultaneously on relief and development issues.

That was a unique vantage point. As the director there, I had the chance to consider how food security programs can build the resilience of communities — through multi-year development programming — as well as its pivotal role in saving lives at times of crises, including conflict and famine. I visited a number of Mercy Corps programs in Africa as the Food for Peace director. In addition, for a time I worked with a nonprofit group in Ethiopia where I was Director for a peacebuilding program; Mercy Corps was a peer organization there that I got to know quite well.

What was it that made you want to move from the government side to the NGO side?

I had spent six years in the office of Food for Peace and really felt like I had done what I had gone there to do. We had dramatically transformed the conversation around U.S. food assistance from being an approach strictly limited to in-kind food to one that uses cash-based approaches as well as in-kind food to meet lifesaving humanitarian needs.

We had dramatically changed the types of food we were providing to improve the nutritional content. We had really driven home the resilience agenda in our development programs as a top priority for the multi-year food security program. And we had been involved in shaping the Global Food Security Act, a major piece of U.S. legislation which has a cash-based food assistance component to it. I just felt like it was time for me to take on a new challenge and let the next round of Food for Peace leaders step in and take the process forward.

What is your greatest concern about food security right now?

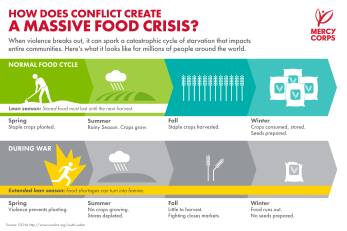

We know the food security situation globally has deteriorated sharply. We know that there are 81 million people across 45 countries in need of emergency food assistance, and that’s up 70 percent since 2015. That is a dramatic change. The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) recently reported that after a decade of improved food security globally, we now have seen deterioration in the last five years. That deterioration is directly linked to conflict.

Get the quick facts about global hunger ▸

It used to be a decade ago that 80 percent of humanitarian response was directed toward natural disasters. Today, 80 percent is going toward conflict. So you’ve had a complete change in what’s driving food insecurity. That intersection of food insecurity and conflict is really at the top of my mind.

Are we seeing any progress in the countries facing the greatest need, particularly South Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Yemen?

You don’t stay in this business this long if you don’t see bright spots in even the worst of settings. I would say that’s certainly been true in my experience — you travel to places and see communities that have been able to maintain their food supply and not require food assistance because of interventions combined with their own resilience. I think you can see some of those bright spots in all of these crises. But fundamentally what’s beneath them is a political crisis that requires a political solution, and that is what has been missing now for a long period of time.

What are the specific challenges of getting food to people in Yemen?

To state the obvious, Yemen is the worst humanitarian crisis on the planet. It’s the largest number of people in the world on the brink of famine: 7 million, probably the largest number in our lifetime and well beyond. A cholera outbreak is impacting a record number of people, almost 1 million. Vaccines and medical supplies are not sufficient, and the threat of wide outbreaks of disease beyond cholera is upon us.

Learn more about the crisis in Yemen ▸

The fundamental problem in Yemen is that 90 percent of what Yemen needs for survival — food, fuel, medicine — is imported. That was true before the crisis. The crisis is fueled by the fact that many of the key ports are closed to both commercial and humanitarian supplies. It really is an access issue and it requires both access to the ports and access from the ports to those populations that are most in need.

With your background and position in DC, how are you thinking about the impact of U.S. policy on development programs?

I’ve been very encouraged by the bipartisan support for both development and relief in Congress, and that has really given me confidence that we can continue to see a strong U.S. voice on these issues.

We know that in the coming year Congress will be asked to reauthorize the Global Food Security Act, which was a milestone piece of legislation that committed the U.S. to help transform the global food system so that we can continue to feed a growing global population. That’s going to be very important. We also know that Congress will be asked to reauthorize the Farm Bill, which is legislation that is vital to Mercy Corps and a lot of other organizations that do multi-year resilience programs.

What is the role of resilience in an emergency? Why is it important to focus long-term, even when responding to a crisis?

The international community has learned this the hard way. If you look at the shocks in east Africa in 2011, when we had a famine in Somalia, the massive drought in west Africa in 2012, and the massive drought in southern Africa due to El Niño in 2015, we know these recurrent shocks are creating widespread suffering, loss of life and very, very high demands on the humanitarian system to respond.

What we know about resilience — and we’ve been able to demonstrate this in research as well as in our own programs — is that communities benefiting from multi-year resilience programs can better withstand these shocks with our help. We know it’s a lot less expensive to prevent a crisis through resilience than to address it through foreign aid once it begins.

I think the consensus is that resilience makes sense. That’s a huge victory and we need to keep going.

"We know it’s a lot less expensive to prevent a crisis through resilience than to address it through foreign aid once it begins."

The flip side is that relief at scale remains important as well because the scope and scale of the crises hitting the world are just enormous. Resilience work takes time. You’re going deeper and narrower in terms of your targeting. The crises are coming too quickly for us to not respond at scale. I do see there’s a role of relief in reinforcing resilience. The approaches that we take that keep local markets open, traders moving and commercial activities underway — like Mercy Corps’ cash-based programming and other activities that support livelihoods in crises — are critical, so I would encourage us not to turn our eye away from relief even as we do resilience.

In your early days at Mercy Corps, what are you most excited about at the organization?

When I started in my career as a refugee officer and then as a disaster response officer in foreign disaster assistance at USAID, I began to ask questions around how we get out of this box of having to give aid to begin with. Resilience is part of the solution, but so is the peace programming work that Mercy Corps does. One of the things that really excited me about Mercy Corps is its unique approach of blending development with peacebuilding and knowing that we need to understand the root causes of conflict if we’re going to be successful in these very fragile settings. I’m very excited about that.

I also really like the way we are blending our research efforts with our program results to inform policymakers and practitioners. I just finished reading a Mercy Corps study on markets in northeast Nigeria that is designed to shape the conversation around what recovery should look like in Nigeria. Similarly, there’s a study I just finished reading on the root causes of violence in Mali and how that should inform our programming. From the outside I can tell you that Mercy Corps is known for being an intellectual leader as well as a field practitioner, and I like that and embrace that.

Regarding our Technical Support Unit, I’ve been amazed at the depth of expertise across more than a dozen sectors, and the way Mercy Corps has forged this unit to be sure that we bring the best practices in each sector to the field, the most innovative ideas and a focus on transformational change.

What do you see as Mercy Corps’ big opportunities in 2018?

I think we bring a unique vantage point to this issue of food security, hunger and conflict. We work in fragile settings and we have gained a lot of knowledge through our multi-year resilience programming, our peacebuilding work and through our growing work in the area of financial inclusion. I think this is a very exciting mix of things that we bring to the question of: if the majority of hungry people are going to be in fragile contexts in the coming decades, what is the proper approach to global hunger and fragility? That’s an area where we bring expertise and there’s an opportunity to really hone our message and our knowledge to inform how the world addresses those issues.

I am really thrilled to be here. I have a long history of looking at the world through a variety of prisms — the relief prism, the conflict and peacebuilding prism, the development prism — and having an opportunity to look at the same problems from different seats has given me a unique vantage point. I really feel that Mercy Corps is a great place to continue that exploration.

Join us

From Nepal and Syria to the Horn of Africa and beyond, Mercy Corps responds quickly to help communities around the world recover after disaster and build a stronger tomorrow.