The facts: What you need to know about the South Sudan crisis

South Sudan should be a country full of hope eight years after gaining independence. Instead, it’s now in the grip of a massive humanitarian crisis.

Political conflict, compounded by economic woes and drought, has caused massive displacement, raging violence and dire food shortages. Over seven million people — about two thirds of the population — are in need of aid, including around 6.9 million people experiencing hunger.

Food security is expected to deteriorate more, with 7.7 million people estimated to face crisis levels of hunger with the onset of the July to August lean season, the period of time between harvests when food stores are low.

The ongoing conflict and insecurity have pushed millions to the brink of starvation for years. In 2017, famine was declared in two counties in South Sudan, and famine has remained a persistent threat since. Without peace and consistent humanitarian access, another famine this year is likely.

The people of this young country need our help, and among the world’s other emergencies, we must not forget them. We are working on the ground to reach families who are struggling to survive in South Sudan — but our lifesaving work starts with you.

Learn more about this complex crisis and get the latest on the situation in South Sudan below. Plus, find out how you can help.

- When did the crisis in South Sudan start?

- What's happening in South Sudan now?

- What's happening to people in South Sudan?

- How bad is the food crisis in South Sudan?

- What are the effects of hunger in South Sudan?

- Why did the humanitarian situation deteriorate so quickly?

- Where have people from South Sudan fled to?

- How are people surviving outside of camps?

- Why is there a food shortage in South Sudan?

- Can people buy more food in South Sudan?

- What is life like in the camps?

- What are the effects of disease?

- What are the most urgent needs in South Sudan camps?

- How can we help people in camps stay healthy?

- Is disease affecting other people in South Sudan?

- Who is most affected by the crisis in South Sudan?

- What will happen if fighting continues in South Sudan?

- Is South Sudan getting enough support?

- How can we help people in South Sudan?

When did the crisis in South Sudan start?

South Sudan gained independence from Sudan in July 2011, but the hard-won celebration was short-lived. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, the ruling political party that originally led the way for independence, is now divided and fighting for power.

In December 2013, political infighting erupted into violence in the streets of the capital, Juba, after South Sudan’s president accused his vice president of an attempted coup. Fighting between the two factions of government forces loyal to each soon moved to Bor, and then to Bentiu.

Violence spread across the young nation like wildfire, displacing 413,000 civilians in just the first month of conflict. Tens of thousands of civilians rushed to seek refuge in U.N. bases that were subsequently turned into makeshift displacement camps.

The fighting has continued, becoming an increasingly brutal civil war and affecting the entire country.

What's happening in South Sudan now?

A handful of peace agreements have been signed over the course of the war — the most recent in September 2018 — but they have been repeatedly violated. While reported incidents of conflict have decreased somewhat since the new deal, the situation in South Sudan remains highly unstable and outbreaks of violence continue.

Relatively small numbers of people have started to return home in light of the tenuous peace agreement, but new displacements continue and overall displacement remains high. Those affected are struggling to survive after years of protracted conflict that has destroyed livelihoods, forced people from their homes, disrupted planting and eliminated critical coping resources, like savings and livestock.

Additionally, inadequate rainfall in 2018 has exacerbated the effects of the conflict and slashed crop production, with only 52 per cent of the national cereal needs being met by recent harvests. More than half of families who could harvest only collected enough food to cover their needs for 1 to 4 months, compared to pre-crisis harvests that would be sufficient for seven months.

On top of attacks and the lack of food, the country's economy is in crisis — the South Sudanese pound has declined in value, and the cost of goods and services has skyrocketed. At one point the inflation rate reached 835 per cent, the highest in the world at the time.

In early 2017, a famine was declared in parts of South Sudan, leaving 100,000 people on the verge of starvation. While famine is no longer declared as of February 2018, an estimated 7.2 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance.

What's happening to people in South Sudan?

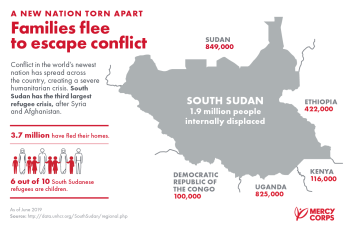

Since the conflict began, 1 in 3 people in South Sudan have been displaced. More than 4 million citizens have been forced to flee their homes. Around 2.3 million people have escaped to neighbouring countries in search of safety, and 1.8 million are trapped inside the warring nation. South Sudan is one of the most fled countries in the world, alongside Syria, Afghanistan and Venezuela.

Those who’ve run have lost loved ones and their homes, their land and their livelihoods. Violence toward civilians has been widespread, including targeted attacks, gender-based violence, kidnappings and murders. Burning and pillaging of homes and livestock is rampant.

And assaults on aid convoys and looting of supplies have become increasingly common, making it difficult — and dangerous — to reach in-need families with the support they need to survive.

Nationwide, hundreds of thousands of young ones are facing an uncertain future — according to UNICEF, more than 70 per cent of the country’s children are out of school. Find out how we get kids to class during conflict ▸

Across the country, children can't learn, people can’t work, farmers can’t plant — all they can do is hope to survive until there is an end to the vicious fighting.

How bad is the food crisis in South Sudan?

Humanitarian efforts have helped prevent widespread starvation, but the situation in South Sudan is desperate again and the number of people facing hunger remains at record levels. After famine ravaged parts of South Sudan in 2017, people are still at risk of dying of hunger. Ongoing violence continues to keep people from their homes, damage markets and disrupt planting, all of which keeps them from getting the food they need to survive.

In May 2019, 6.9 million people were already at risk of going hungry and, without humanitarian support, that number could increase to more than 7.7 million in the coming months. If it does, it would be the highest number of people ever to face food insecurity in South Sudan.

The upcoming lean season, the period between May and July when stores from the previous harvest are running low but the next is not yet ready, will be particularly threatening for vulnerable families.

What are the effects of hunger in South Sudan?

Hunger anywhere can have long-term, debilitating consequences, but it can be particularly threatening during a complex crisis like the one in South Sudan.

When people go hungry, they have trouble staying healthy and become more vulnerable to dangerous diseases, which is a weakness people sheltering in makeshift camps and communities can’t afford. Their bodies are also not as strong or productive as they could be, which makes it difficult for them to work, find food and keep their families safe at a time when they urgently need the strength to do so.

Children’s development is also seriously impacted by hunger. Without proper nutrition, they don’t hit critical developmental milestones, which can permanently inhibit their ability to learn and function for the rest of their lives. Hungry children don’t learn as well, and they are also at a higher risk of disease. According to UNICEF, around 860,000 children under 5 in South Sudan are acutely malnourished.

Why did the humanitarian situation deteriorate so quickly?

South Sudan was once a semi-independent region in Sudan, only recently gaining independence as a country in 2011, after a brutal civil war that lasted more than 25 years. The conflict in December 2013 reopened deeply-rooted political and ethnic tensions that hadn't yet been reconciled in the young country — and those divisions have continued to fuel ongoing clashes.

After those decades of conflict, South Sudan was and still is one of the least-developed countries in the world, which has further complicated the situation.

The larger cities in South Sudan had experienced some development, but the majority of the nation is rural. Even before the crisis, more than half of its citizens lived in absolute poverty, were dependent on subsistence agriculture and suffered from malnourishment.

"I am afraid we have lost our future and everything we worked so hard for to win our independence," says Chudier from the displacement camp where she's seeking safety. "We worked hard to build a life here [in South Sudan] and have beds to sleep on, blankets and plates to eat off. Now it is all gone.”

“I just want peace and to be able to take my family home, so they can have a normal life," she continues. "I spent most of my life as a refugee, I don’t want my children to grow up like I did.”

Because the economy was already fragile before fighting began, people like Chudier have very few resources to help them survive the long-term conflict and displacement they're now faced with.

Plus, at this point in the war, many people have had to flee for safety more than once. Repeated displacement makes it impossible for people to regain any sort of stability — if they do manage to make progress by planting crops, purchasing animals or rebuilding livelihoods in their places of refuge, they must quickly abandon them if the fighting forces another escape.

South Sudan also has very little formal infrastructure — roads, buses, buildings — which makes it difficult to transport food and supplies. Many towns and villages become inaccessible during the annual rainy season due to closed airstrips, washed out roads or lack of roads altogether, sometimes limiting any delivery of humanitarian aid to the isolated areas that need it most.

These logistical constraints, combined with the violent context, make reaching people with the humanitarian support they desperately need incredibly challenging and risky. Over the course of the crisis, South Sudan has become one of the most dangerous places in the world to be an aid worker.

Where have people from South Sudan fled to?

An estimated 2.3 million people have crossed into neighboring countries including Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda, resulting in Africa’s largest refugee crisis. Inside South Sudan, 1.8 million people are displaced. A small number of people have reportedly returned to their villages where there is relative stability, but most remain in their places of refuge and ongoing, sporadic attacks continue to force more people to flee for safety.

The majority of displaced families live outside the camps, wherever they can find safe shelter — often in small villages that offer some security, tucked away from the main areas of fighting. For those running from violence, there is no other choice but to flee into the bush with what little they can carry with them.

How are people surviving outside of camps?

Many families who've fled their homes have had to move multiple times to escape the spreading violence.

Some run into the bush, with their children on their backs and little or nothing else. In the bush, there is often nothing to eat but wild plants like grass, roots and water lilies. But some people would rather face the risk of starving than endure the violence that has been rampant in towns and villages.

For others, finding shelter in an isolated, small village, removed from the violence, is the best they can hope for. Those villages offer some sense of safety, but there is little in the way of food or supplies, and always the risk that fighting will come and families will have to flee yet again.

Learn how we get to South Sudan's hardest-to-reach families ▸

Small food rations given out by aid organisations help somewhat, but escalating attacks on aid convoys and the annual rainy season make deliveries difficult and infrequent — not enough to count on.

Mercy Corps is providing seeds and tools and helping to restart markets in small villages so food can be grown and accessed by families sheltering in rural areas.

Why is there a food shortage in South Sudan?

South Sudan has agricultural potential, but due to poor infrastructure and lack of technology, growing enough food to feed everyone in the young nation has never been easy. After decades of struggle, food security was starting to improve before the current conflict began. In 2013, harvests of staple crops like millet, maize, and sorghum were up 20 percent (FAO).

Unfortunately, the crisis in South Sudan has disrupted farming and any hard-earned improvements have been lost. Because of the fighting, people who would normally grow crops have been far away from their land, running and hiding from violence — unable to plant. Conflict has also reached the Equatorias, the area considered the breadbasket of South Sudan, which is exacerbating the food shortage.

As conflict continues, many families are still far from home and unable to plant seeds, prepare land or harvest their crops. At one point, about half of all crops were in violence-ridden areas.

Can people buy more food in South Sudan?

Because of what's happening in South Sudan — violence, instability, recurring displacement — food stores are running out and many markets are empty. The threat of possible attacks, plus the high cost of transport and struggling economy, has hindered trade of food from safer areas.

Plus, what little food is available has soared in price, and most displaced families have no money to buy any goods. While overall food prices are lower than last year, costs remain well above average throughout the country: in Juba, the price of sorghum is 203 per cent higher than the five-year average, and in Wau, it’s 581 per cent higher.

Many families have lost their livelihoods, and purchasing power is extremely low. In Wau, it is estimated that nearly half of a day’s wage would need to go toward food to meet the average family’s needs, and most people are unlikely to have access to labour opportunities on a daily basis.

What is life like in the camps?

While there may be relative safety in the six U.N. camps, the conditions there are insufficient.

The camps were not designed to host this many people for so long. Proper sanitation, hygiene and waste disposal are inadequate in such crowded conditions, and heavy seasonal rains flood many of the camps, making things even worse.

What are the effects of disease?

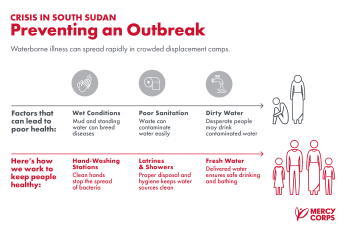

Beyond making everyday activities like sleeping and preparing food extremely difficult, heavy rains and standing water also increase the risk of disease.

Communicable and waterborne diseases like cholera and malaria spread quickly in these conditions. The risks are also high for other infections caused by contaminated water, malnutrition and weakened immune systems. Children are hungry and thirsty. If they get desperate, they may end up drinking dirty water that could give them an infection. For a young child, an infection can lead to weight loss, severe dehydration and even death.

Outbreaks of cholera and measles have already been reported, and the presence of Ebola in neighbouring countries poses a threat as well. Flare-ups are already ongoing in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where more than a combined 900,000 South Sudanese refugees are sheltering.

What are the most urgent needs in South Sudan camps?

Displaced families receive some food, but there are urgent needs for additional food and disease prevention through better sanitation and access to clean water.

How can we help people in camps stay healthy?

To help prevent outbreaks, better sanitation and clean water are critical. We’re building latrines and hand-washing stations, teaching proper hygiene and providing clean water, helping hundreds of thousands of displaced people stay healthy.

Building latrines and teaching proper hygiene and waste disposal are the best ways to ensure that water sources stay clean for people to drink, cook and bathe. Read more about our hygiene response ▸

Is disease affecting other people in South Sudan?

Yes. In 2018, outbreaks of measles, meningitis and Rift Valley fever, a viral zoonotic disease, were reported in areas across the country and resulted in deaths. In 2019, the number of reported measles cases was six times higher than in 2018.

Nationwide, disease outbreaks are reaching new areas and lasting longer. The country suffered a protracted, widespread cholera outbreak between June 2016 and February 2018, with more than 20,000 suspected cases and at least 436 deaths. It was the longest cholera outbreak in South Sudan’s history.

Additionally, medical care to cope with these risks is increasingly out of reach. Medicine is in short supply, and health workers and medical centres have been routinely targeted. Last year it was estimated that only around 20 per cent of South Sudan’s health facilities are fully operational, and a meager 20 per cent of the population can reach a hospital within 24 hours.

Who is most affected by the crisis in South Sudan?

Women and children are disproportionately impacted by the conflict in South Sudan. The majority of the population of the United Nations’ displacement sites is made up of women and children, with more than 60 per cent of South Sudanese refugees being under age 18.

Additionally, sexual violence toward women and girls is pervasive. The United Nations recently reported a surge in sexual attacks, including women and girls experiencing abuse during raids on their homes, while they are fleeing or when they leave their shelters to search for basic necessities. The people committing these crimes are rarely held responsible.

To make matters worse, women and girls continue to bear the burden of family caretaking even during crisis. In the face of heightened violence, recurring displacement and loss of livelihoods, daily tasks like collecting water and firewood can make them continual targets for attack.

What will happen if the fighting continues in South Sudan?

Without peace and support, the crisis in South Sudan will continue to deteriorate. Families will remain in hiding away from their homes and their land, unable to plant, and the economy will decline further.

The number of people at risk of hunger will increase. Families will die from starvation, malnutrition and disease.

Is South Sudan getting enough support?

The short answer: no. Humanitarian appeals to provide support to South Sudan have been chronically underfunded.

The UN appealed for £1.32 billion to assist people in need in 2018. Only 68 percent of the budget was funded.

In 2019, the UN is appealing for £1.15 billion to provide critical support. Their request is so far only 30 per cent funded, but it must be fully funded in order to reach the millions in need across the country.

Many humanitarian organisations, including Mercy Corps, are partnering with the UN, using both private contributions and funding from the international community, to address the urgent needs of innocent people in South Sudan.

There are many crises we are working to address, but this young and vulnerable country needs more help to avoid further catastrophe and human suffering.

How can we help people in South Sudan?

Mercy Corps is working to provide desperately-needed latrines, showers, hand-washing stations and clean water to help people survive and prevent the spread of diseases like cholera in camps and communities.

In the small villages where many people are sheltering, we have rehabilitated living spaces, provided seeds, tools and training so people can grow food wherever they are living, and implemented cash-for-work programmes to give vulnerable families some money to purchase supplies.

We're also distributing emergency funds to help traders and families access goods in hard-hit areas of the country. And our emergency education programme trains teachers, repairs schools and provides school supplies and free meals so children can continue learning despite this crisis. In one refugee settlement in Uganda, we're providing cash aid that will allow refugees to buy what they need most while also stimulating the local economy.

Learn more about our cash aid programme▸

But the South Sudan crisis remains dire, and the needs of displaced families are increasing.